PART II. ERA OF HUNTER-GATHERERS

PART II. ERA OF HUNTER-GATHERERS

“Indeed, want and hunger were not the only reasons for fighting. Plenty and scarcity are relative not only to the number of mouths to be fed but also to the potentially ever-expanding and insatiable range of human needs and desires. It is as if, paradoxically, human competition increases with abundance, as well as with deficiency, taking more complex forms and expressions, widening social gaps, and enhancing stratification.”

– Dr Azar Gat. War in Human Civilization (pg.32)

This is how we lived for the majority of our time here on Earth. In some sense, it is the evolutionary natural way of life, termed the ‘state of nature’ in political philosophy. We hunted for food and fought for survival; we did what every other animal on Earth did. How did we then, a random species of apes, rise to be the most proficient killers on this planet?

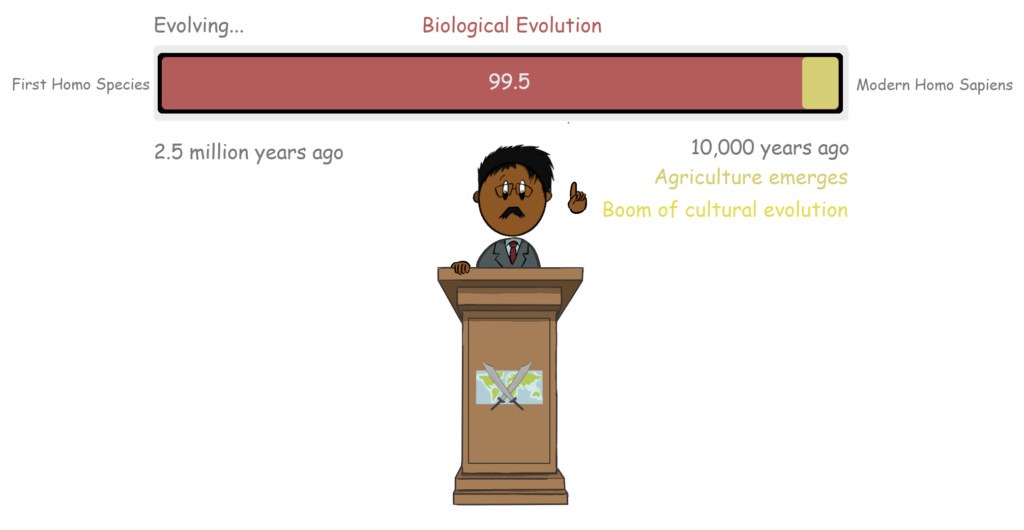

Three million years ago, to around 30,000 years ago, species of the genus Homo engaged in a ‘simple’ hunter-gatherer form of lifestyle. Following this, till around 10,000 years ago, ‘complex’ hunter-gatherers, uniquely Homo sapiens, bridged the gap between the pure hunter-gatherers and the new agriculturalists. We shall look at the purpose of armed conflict in both these ways of life and how it may have shaped future transitions in human history.

THE DREAM LABORATORIES

AUSTRALIA: SIMPLE HUNTER-GATHERERS

At the time of the European arrival in Australia, no pastoralists or agriculturalists existed. An estimated 300,000 hunter-gatherers, distributed in 400-700 regional groups, lived on the continent. Due to the geography of Australia, this laboratory of hunter-gatherers was one of the few pre-state societies studied that had relatively no outside interference. We can classify the people living in Australia then as ‘simple’ hunter-gatherers, living closest to the human state of nature. Not a single one had even used a bow, a device that significantly advanced human’s first-strike capability. However, archaeological evidence does point to the use of spears, clubs, stone knives, boomerangs, and wooden shields. The shields being the only specialized fighting device rather than a hunting one.

An additional factor to consider is the population density, as it provides insight into the link between resource scarcity and warfare.

Australia’s coastal and lush regions had 2-6 people per kilometre square. Compare this to the world’s current population density of 55 people per kilometre square. Even in the least populated desert areas of central Australia, where it was one person per 50 kilometres, there was no common land of idyllic peace. Territories had been drawn up and existed from ancient times, supported by totems and myth. Trespassing was considered a sacrilege and would meet an aggressive response involving a demonstration of power or violence itself. A pitched battle fought between the Waringari and Walbiri tribes showed that claims on native wells were reason enough to invade another territory.

In well-watered environments, hunting game and food became the priority. Starvation and death loomed over the heads of these hunter-gatherers on a daily basis. It became essential to secure resources for the present and the future of their family, even at the expense of another.

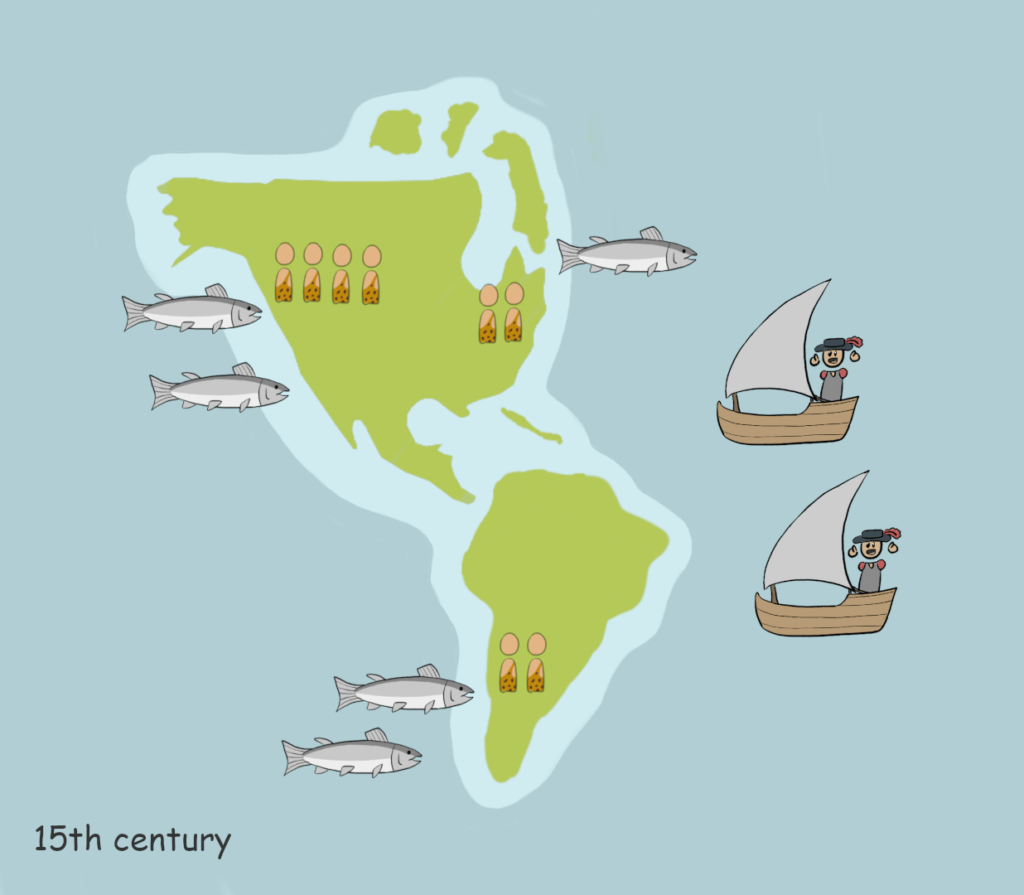

These primary biological resource needs became the first level causes of conflict among humans. The second level causes of war originate from these very primary needs and desires, and are activated through relative abundance or scarcity. To understand the connection, let us look at the continent of North America during the European arrival in the 15th century.

NORTH AMERICA: COMPLEX HUNTER-GATHERERS

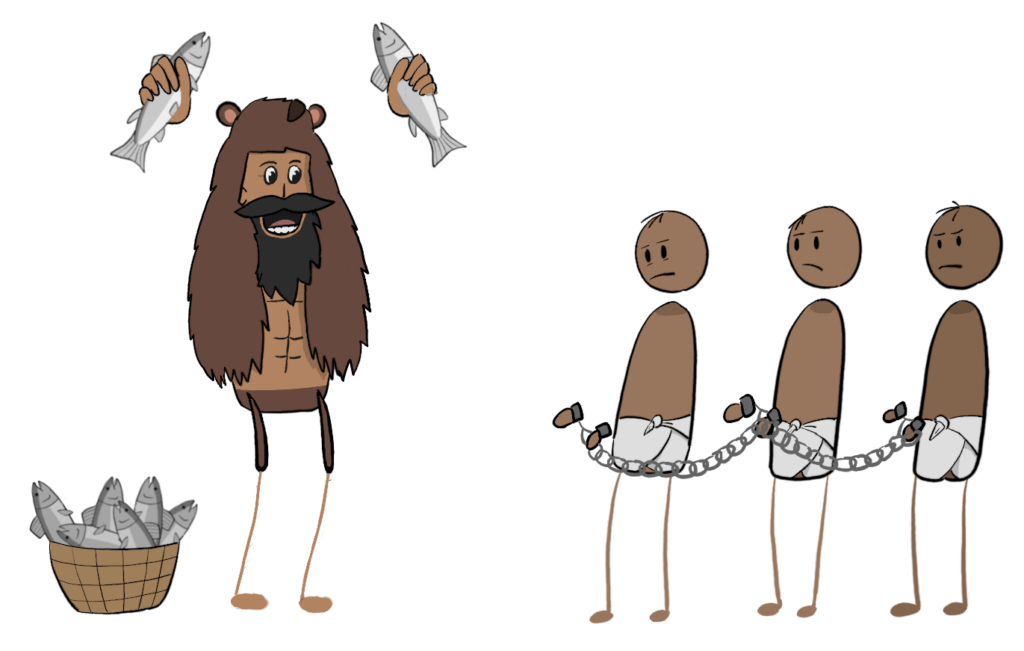

North America’s west coastline is home to rich marine resources, especially the salmon. Additionally, wild game was abundant on land as well. This allowed permanent settlement and high population densities around these pockets of plenty. The people who controlled the richest sources were conveniently better off than the others. Resource hoarding and territorial control by way of force became the foundation for developing social hierarchy within these societies, giving rise to a new class – ‘the big men’. These men would be associated with more wealth, women, and martial prowess. The competition that this created influenced violent conflict due to an interesting paradox. Deficiency of resources would cause conflict, but even abundance could be a trigger. This is due to the ever-expanding and insatiable range of human needs and desires. Dr Gat states, “it is as if, paradoxically, human competition, increased with abundance, as well as with deficiency, taking more complex forms and expressions, widening social gaps, and enhancing stratification.” Now, war was a path to slave labour and territorial gains to further one’s resource accumulating capability. Or, it was a path for the unfortunate to create resource accumulating potential.

Why big ‘men’ though? Were there no big ‘women’? Even today, many modern feminists argue that it was male’s violent tendencies that caused most if not all of humankind’s horrific wars. Recent statistics are some proof of the matter and show that most recorded female violence is done against male violence or under male leadership. Cross-cultural studies on humans show that the second most distinctive characteristic between males and females, after childbearing, is that of serious violence. Are men adapted for this, or is it a just a result of social conventions?

MAN THE BEAST?

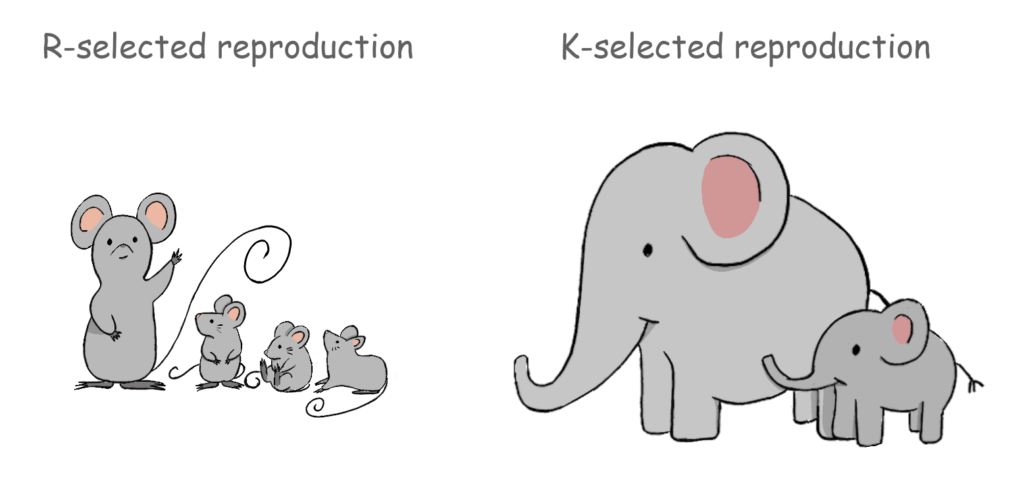

Part I of this series covered the fundamental asymmetry between males and females with respect to their reproductive strategies. Females with a logistical barrier of few eggs and the ability to produce offspring only once at a given time had to rely on the ‘quality’ of mate, while males having no logistical barrier seek to enhance the ‘quantity’ of sexual partners in their life. Therefore, the key limiting factor for a male is competition from other males. The violent competition for females and the necessity to obtain strong survival genes by females made strength, size, and risk-taking behaviour recursive replicating forms within the male sex. Let us see how this influenced Homo sapiens in particular.

Human beings are bipedal creatures. The reasons for which are a plethora of factors, one of which was the need to accommodate a larger brain. However, bipedalism reoriented the birth canal and resulted in a relatively earlier foetal birth than quadrupeds. Due to which, human offspring mature slowly in nature. This makes it necessary for the infant to obtain protection from both the parents during the helpless development stage in its life, making cooperative breeding or pair bonding a preference in humans. A male’s loyalty and ability to provide, protect, and survive became highly desirable qualities to females. This increased post-copulation investment by the males became one strategy to even out the reproductive asymmetry while also making sex specialisation possible. Division of labour caused women to focus on foraging close to home, making them the last line of defence in case of an attack. Women also played a prominent role in the child-rearing process due to their ability to provide for the child’s nutrition. While men specialised in long-distance hunting and in fighting to defend the family or settlement. Those who were bigger, stronger, and more ferocious would have more success defending their homes, allowing their genes to carry onto the next generation successfully.

Males had no other option other than to run or fight against the enemy. By contrast, female scarcity made them highly valuable as a resource to the enemy. The story of Moses’ command (Numbers 31. 17-18) exemplifies war conduct throughout history: kill the men, rape the women, take the young and beautiful as war trophies. Women taken alive had other options for survival – submission, cooperation, and manipulation. Understanding people and being more in-tune with the situation would aid in their quest for survival, making a heightened ‘attention to detail’ and spatial memory beneficial adaptations – the basis of the ‘female intuition’. In contrast, males developed an enhanced spatial orientation as a result of fighting and hunting.

To conclude, the long-standing and mutually reinforcing evolutionary strategies and biological adaptations in males and females made it such that men would be more predisposed to fighting than women. However, these predispositions are strongly regulated by evolution-shaped motivational complexes that come into play under relative abundance or scarcity and act as the second level causes of violent conflict.

EMOTIONAL BEINGS

STATUS, POWER, AND DOMINANCE

Abundance and scarcity introduced social hierarchy and status in early societies. The big men who controlled the resources through way of force were also able to become the dominant propagator of genes through polygamy. This behaviour contradicts the human biological disposition to pair-bonding, but was made possible due to resource accumulation and the ability to feed and shelter more wives. Having a bigger family also entailed having more kin-based ties and a larger group, resulting in a larger defensive or invasive force. Success with resource acquisition contributed to an increase in status and power, which in turn enhanced one’s access to resources and matrimonial opportunities. To maintain this dominance, the big men developed a preference for male children. Causing female infanticide to be incorporated in the fear of resource scarcity, exacerbating the already present female scarcity! This, in turn, enhanced the male competition for women, resulting in more violence. On the other hand, monogamy distributes the reproductive capacity more evenly among men. This does not entirely remove violence as a tool to obtain women, as abduction and rape, even of other male’s wives, still existed as a tool to further one’s reproductive capacity. However, according to a cross-cultural study, monogamy did reduce the amount of internal warfare compared to a highly polygynous society. This is credited to the correlation of violent male death to female scarcity.

A vicious cycle took hold here – individuals resorted to polygamy and female infanticide to increase the number of males who could fight for them, reinforcing the scarcity of females and violence among males. Having fewer wives or raising female children would have solved both issues by alleviating female scarcity and reducing in-group male violent competition. Here, the rationale choice of the individual mind conflicted with the common good. This is a perfect example of the ‘prisoners dilemma’ in game theory, which holds the key to understanding one of the most interesting reasons for violent conflict – revenge.

REVENGE – TO DETER OR ANNIHILATE

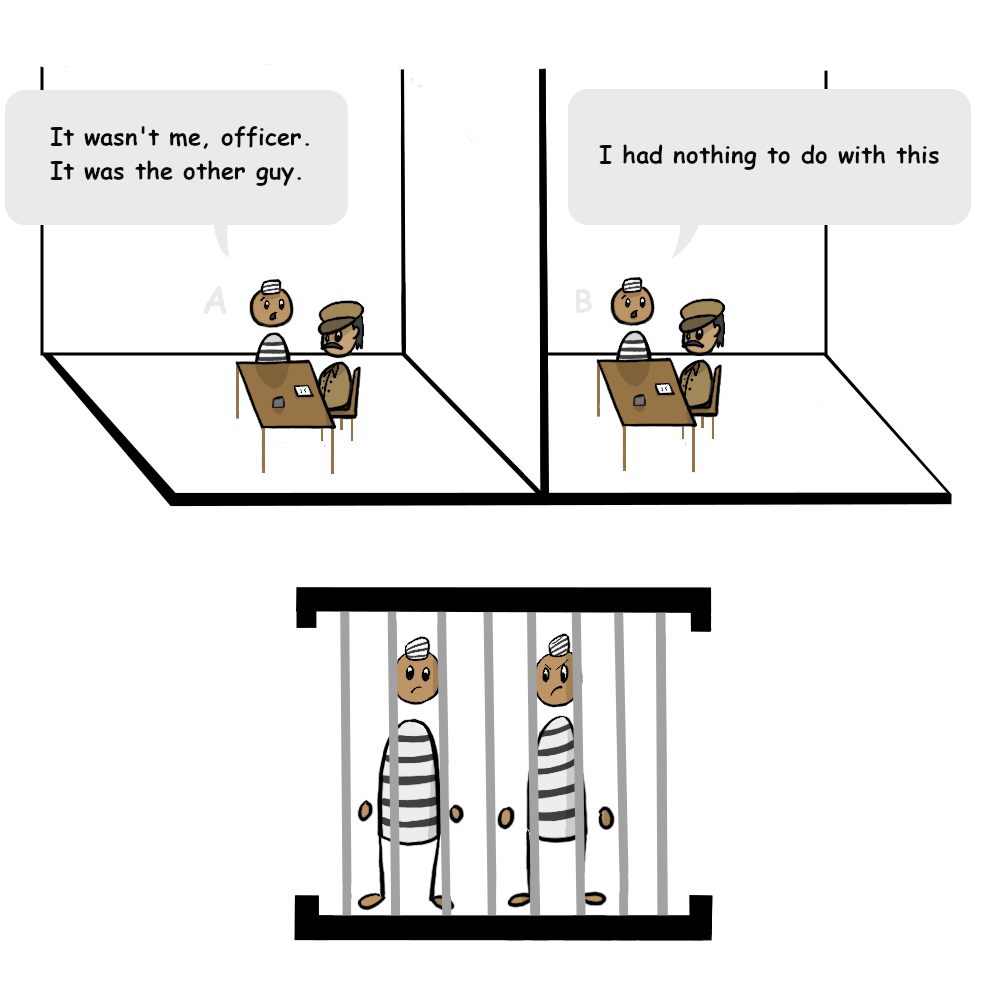

THE PRISONER’S DILEMMA

The Game:

Two prisoners, A and B, are being interrogated about a crime they jointly committed. Each prisoner has three options –

(i) defect and blame the other

(ii) keep silent

(iii) confess

If A chooses to blame B, A goes free, and the accomplice B, who kept silent, gets a heavy sentence. If both A and B confess or blame the other, they are given a heavy sentence, perhaps moderated by their willingness to comply. If both A and B keep silent, there will be little to go on, and the authorities will give both light sentences, the best result for the prisoners. However, what is the most rationale decision an individual can take in this situation?

The logical decision here is to blame the other, because, unable to establish cooperation with your accomplice, this option is best regardless of their choice. However, if both select this option, they both end up with a heavy sentence. In contrast, if they had kept silent, they would be let off lightly. This highlights that the optimal choice under isolation is, in fact, inferior to the optimal choice had there been mutual cooperation secured. The prisoner’s dilemma provides great relevance and insight into the cycle of war and animosity. Although, it is important to note that the prisoner’s dilemma comes into play only when a decisive result cannot be obtained or obtained through terrific costs. Submission and acceptance of humiliation are at times preferred over the risk of retaliation, especially against a much stronger opponent. However, in isolation, retaliation is often viewed as the most rationale choice, as a lack of it could invite more injuries or even new attackers.

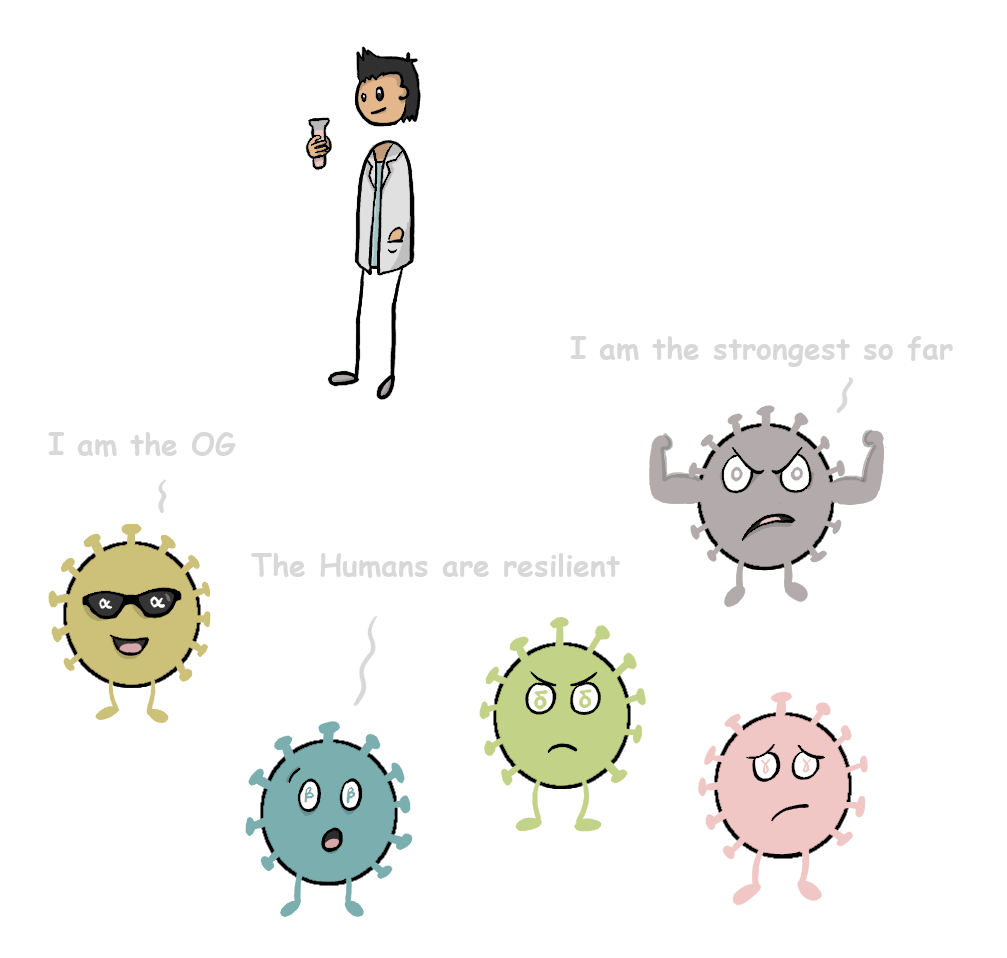

The source of these retaliatory conflicts, or the quest for vengeance, does not arise form the first level causes or from direct conflict itself, but from the fear, suspicion, and insecurity created by the potential of those first level causes for conflict. The fear of war breeds war, even if there existed no real hostility. The escalation of the arms race in nature results from this motivational system, leading to faster cheetahs, taller trees, more deceitful viruses or more immune hosts. In many cases, every step taken to improve upon the existing fighting capability is matched by a counter step by the other.

Increased resources are poured into this seemingly unending quest for an advantage, giving rise to the ‘Red Queen effect’, wherein both sides run faster and faster only to find that they themselves are staying where they were. In international relations, this principle expands further as the ‘security dilemma’, wherein states stay suspicious of each other and preemptive strikes may be launched in the name of defence. The prisoner’s dilemma in nature and the modern world is that if either side gave up their quest to outpace the other, they could save themselves heavy costs that cancel each other out. But this is often not the case because of faulty communication and lack of regulated competition.

The massive first-strike capability of humans blew the prisoner’s dilemma out of proportion. The side that strikes first would have a considerable advantage, forcing one to pre-empt in most cases. If the result is good, it would deter future enemies and ensure security; if not, tit for tat follows until mutual deterrence through attrition gets established. This cycle made primitive humans indulge in stealth raids more often than not, as humans caught off guard were extremely vulnerable. When pitched battles would occur, they would involve spear throwing from afar and demonstrations of power, as opposed to brutal onslaughts. Consecutive innovations in battle tactics and the introduction of ranged weapons would further enhance humans’ first-strike capabilities. We shall look more into this in the next part of the series.

HUMAN ALTRUISM: KINSHIP AND ETHNICITY

First, we need to understand the structure of an average hunter-gatherer society. What held each group together? And how larger groups may have formed.

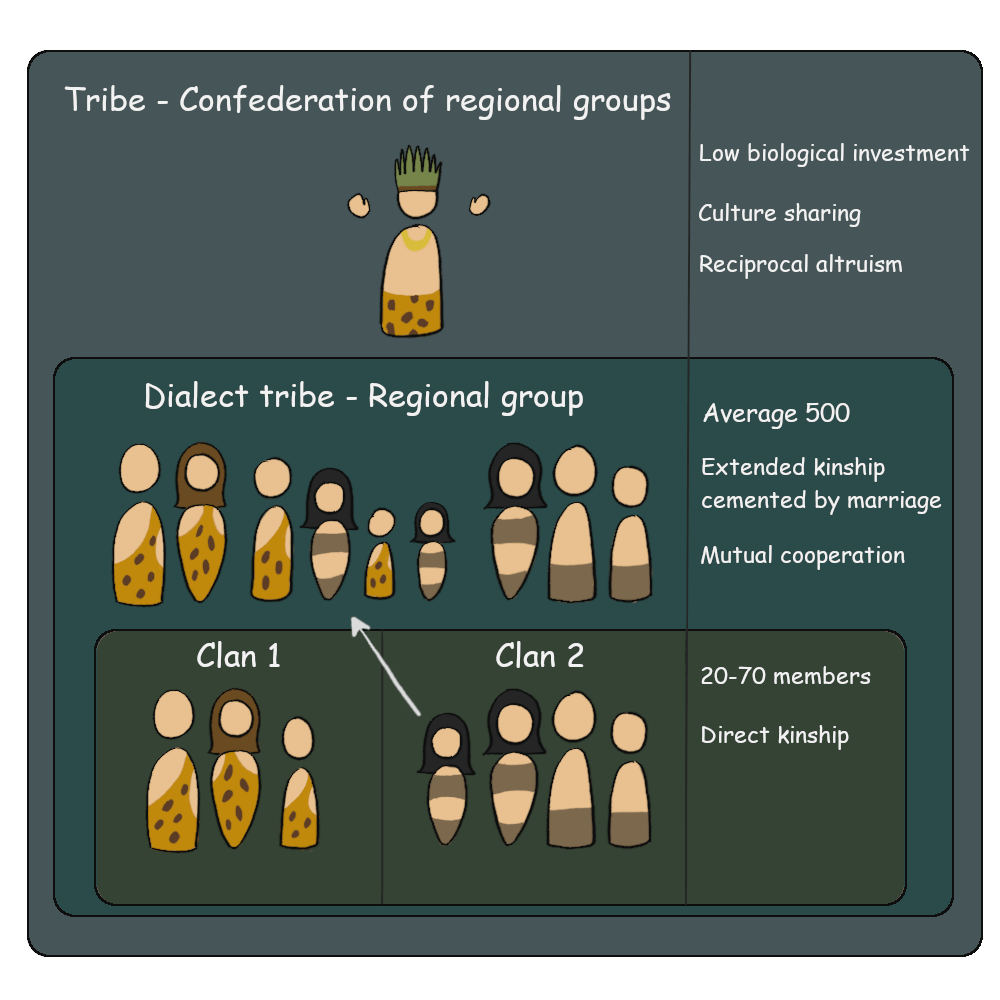

The basic social unit in a hunter-gatherer society is the clan or the extended family group. While evolutionary theory strongly encourages the propagation of one’s own genes, it also inspires the preservation of one’s existing genes in conspecifics. The survivability of the genes shared within a clan becomes the evolutionary justification for seeking cooperation and sustaining risks for one another. For instance, siblings, parents, and offspring share 50 per cent of their genes, half-siblings 25 per cent, and cousins 12.5 per cent. Therefore, it makes sense in an evolutionary perspective for one to sacrifice itself for the survival of more than two brothers, four half-brothers, or eight cousins.

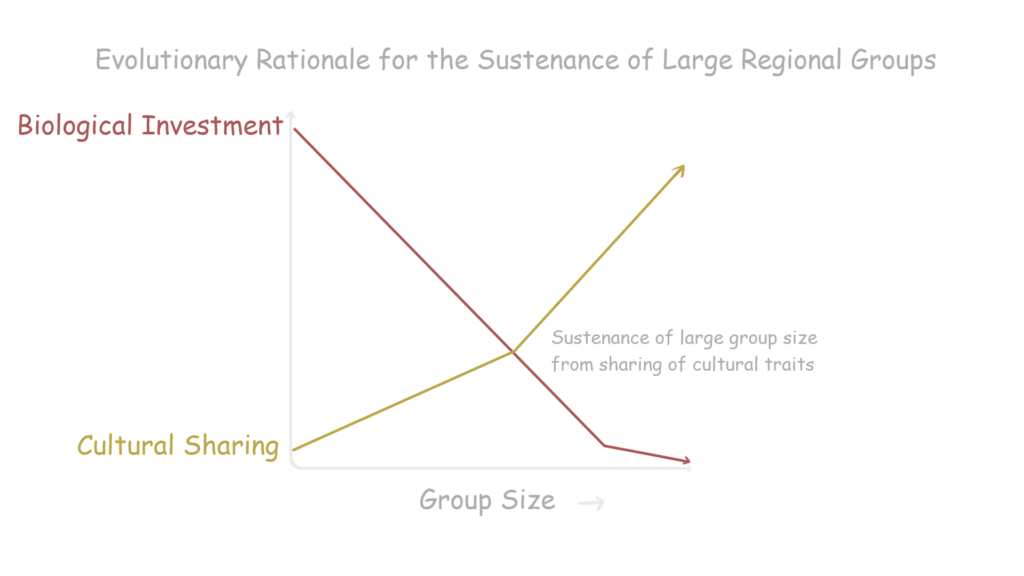

A larger social unit is a regional group or a dialect tribe, unique to the modern Human. This involves multiple clans bonded together with the promise of mutual cooperation. The principal incentive to protect a separate clan is created by the evolutionary ‘investment’ made by individuals who pass on the clan genes by way of marriage into another clan, leading to offspring that both families are genetically invested in. Most hunter-gatherer societies are patrilineal, wherein females come from outside the family. Kinship extends in this way to encompass more and more clans to a point where a regional group is created. However, the biological evolutionary reward steeply declines as the per cent of shared genes reduces. This is because large regional groups are too recent of a development to have had an effect on biological mechanisms. A famous Arab proverb symbolizes this best: ‘I against my brother; I and my brother against my cousin; I and my brother and my cousin against the world.’

So how then does one get a large group of cooperative humans? Enter culture. The sharing of cultural traits among multiple tribes allows for the further extension of human social cooperation, eventually forming a confederation of regional groups or a tribe.

Once cultural sharing reaches a plateau, it diversifies rapidly. Making preservation of the group’s culture as important as the preservation of one’s genes. This fact provides the basis of ‘ethnocentrism’, which creates a drastic bias between one’s own culture and other alien ones. Common extensions are nationalism, racism, and xenophobia, which could all eventually lead to war.

In large groups, it becomes possible for one to reap the benefits of cooperation while avoiding one’s share in the costs – the ‘free rider’ problem in social sciences. For this reason, subgroups of a larger group will hold each other accountable and expect aid in return for their aid. If one party fails to deliver, they risk the chance of being ostracized from the cooperating system. In human relations, this is expanded as reciprocal altruism, wherein goodwill is used to sustain cooperation between parties of a much larger entity. Therefore, culture plays a crucial role in developing cohesion in large non-kin-based societies and in uniting them under a common cause for war.

CONCLUSION

The need to preserve and propagate one’s genes, first-level causes, further extends to develop emotion-based motivational mechanisms, second-level causes, to incite warfare. In those gene-sharing groups that prospered under warfare, aggression becomes an emotional predisposition, reinforcing the culture sharing made possible by the biological adaptation of teaching and learning. These groups would attempt to minimize conflict within themselves and direct it outward. As they would evolve, from family to clan, from regional group to tribal federations, eventually forming states, empires, and nations, the offensive first-strike capability would grow proportionally, piling up the death count of war.

PART II. ERA OF HUNTER-GATHERERS Read More »