PART I. RISE OF THE HOMO SAPIENS

“Thus evolutionary theory reconstructed the question of fighting in the following way: it suggested a deeper natural rationale for fighting and, by inference from that rationale, claimed, in a previously unnecessary way, that this tremendously deadly and wasteful behaviour was somehow carried out in a manner that promoted survival and reproductive success.”

– Dr Azar Gat. War in Human Civilization (pg.42)

Four billion years ago, planet Earth witnessed a revolutionary event that dramatically altered its future compared to its cosmic kin. Today, as far as we know, it is the only planet to harbour life. Though despite the variation life has taken in the form of countless species, one has come atop all. The plan for domination of Earth’s ecosystems by Homo sapiens had been set in motion much before their emergence 300,000 years ago. Humans today are widely considered the most ruthless and dangerous of all animals. What makes us so exceptional? To understand this supposed exponential bellicosity in man, we need to understand the role of violence and killing in the animal kingdom.

BEASTS AND MEN

Most interspecific killings are carried out for prey, like in human hunting. This discussion, however, is more concerned with intraspecific conflict and competition. Violence between mature males constitutes the majority of intraspecific animosity. The main reasons for violent conflict are resources and females. However, intraspecific ‘killing’ depends on the lethality of the animal — first strike capability. In the natural environment, even a slight disadvantage in the form of wounds can significantly diminish the animal’s capacity to obtain food and therefore, shorten their life expectancy. Due to this, animals usually decide to cut their losses and retreat at some stage in a violent conflict. Self-preservation comes first.

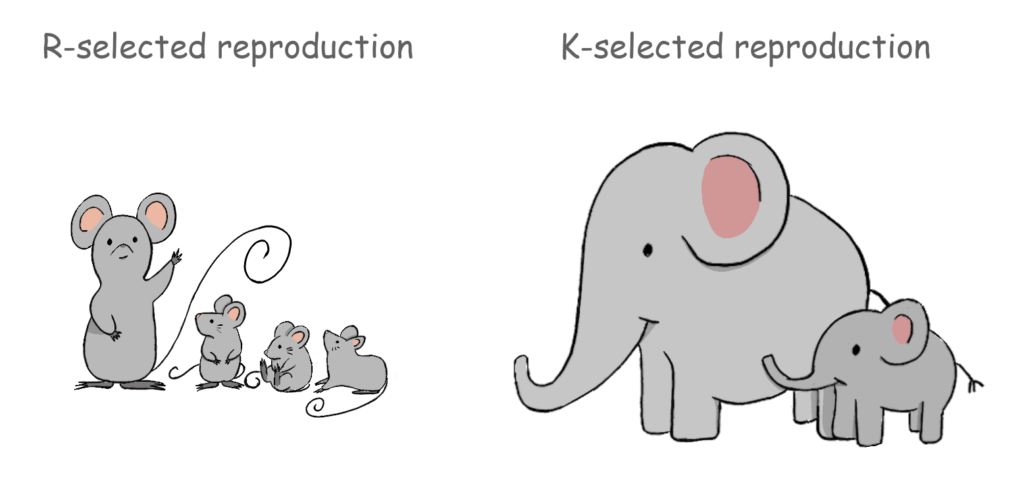

The group most vulnerable to intraspecific killing are not mature animals but infants, where the adult has a significant advantage when it comes to lethality. For example, when a new alpha in a lion’s pride systematically kills all the cubs of the previous monarch. Langur monkeys and gorilla males display similar behaviour. Intraspecific elimination of infants, chicks, and eggs, even by females, is widely observed to reduce potential resource competition. Additionally, young animals often fiercely compete for nourishment, leading to merciless killing during food shortages. This behaviour is displayed more often by animals that use the ‘R’ strategy of reproduction, which entails more offspring and less parental care, in contrast to the ‘K’ strategy of reproduction.

We can see that intraspecific violence is not uncommon in the animal kingdom. The scale of intraspecific killing may vary between species, but it is still more the norm than the exception. Which brings us to evolutionary theory to explain the rationale for this deadly conspecific activity we indulge in.

EVOLUTION AND NATURAL SELECTION

Darwin’s theory of evolution proposes that every organism participates in a vicious competition in nature, the winners of which get shelter, food, water, and the chance to reproduce. This competition is termed ‘natural selection’ and occurs between organisms of different species and within the same species. Random ‘mutations’ appearing in the offspring are the driving force behind the theory of evolution; they permit the introduction of new strategies in nature to cope with changes in the survival calculus. Successful strategies allow individuals to fulfil their somatic and reproductive needs, permitting replication of those strategies in their offspring as well. However, the unfortunate thing about evolution is that it does not entail ‘improvement’ but pushes towards increasing ‘complexity’. One can see this from the limitless variation in flora and fauna around us, much like how Darwin came to the conclusion. Evolution believes more options are better, working somewhat like brainstorming. This recursive reproduction of replicating forms is inherent to evolution, which variates to certain degrees based on selective ‘biological’ or ‘cultural’ pressures.

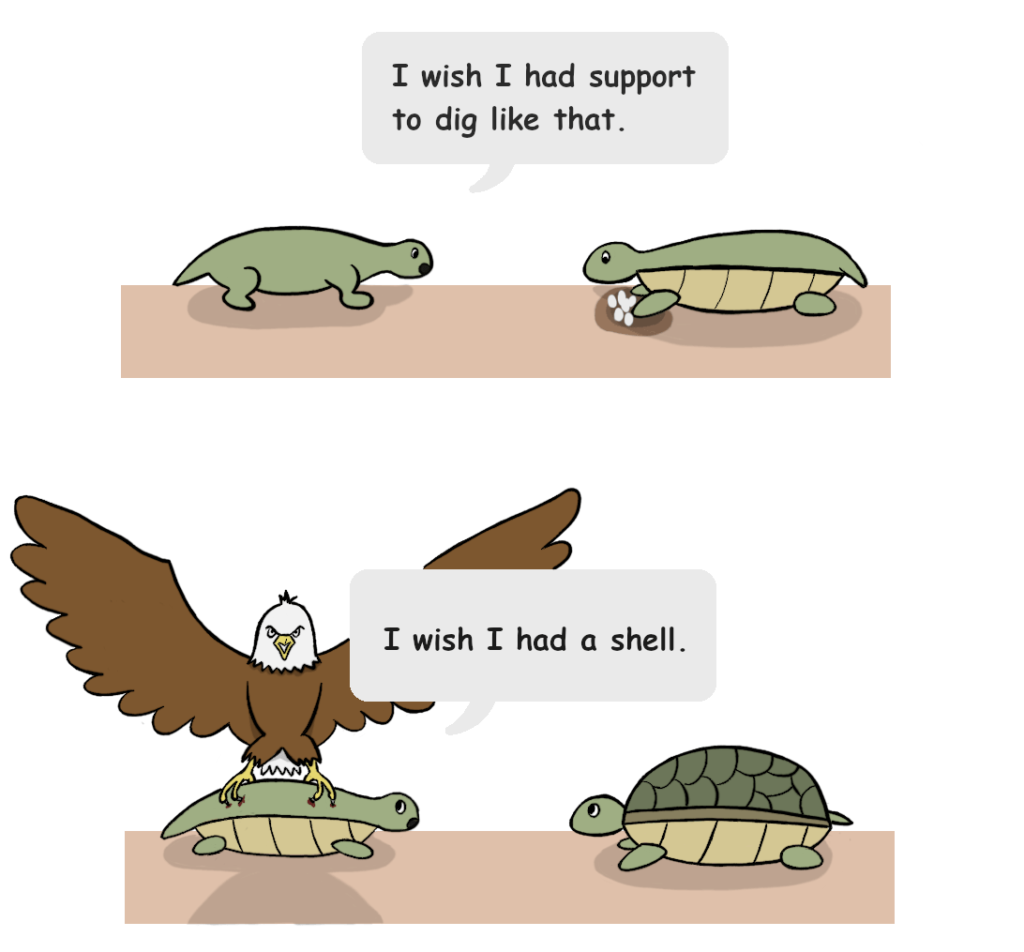

Biological and cultural adaptations mutually interact to co-evolve and take the form of innate traits or predispositions that persist within groups when proven successful in the wider competition. For example, the turtle first developed thick ribs to aid in digging deeper and thereby successfully protect the eggs. Then it evolved to develop a shell from those ribs to defend itself.

VIOLENCE AND AGGRESSION

The strategic development of violent conflict resembles the evolution of a turtle’s protective shell. Unlike competition, which runs parallel with other species in the quest for an advantage, a conflict involves direct action against competitors to sabotage the competition. If physical injury is the goal of said action, the conflict becomes violent. Since conspecifics share the same ecological niches and pursue the same mates, the intraspecific competition could force the hand of some species to resort to violence, thereby significantly reducing the competition by eliminating others. Successful proliferation further strains the scarcity of resources, refuelling the contest for said resources. Therefore, there is no real ‘justification’ for fighting other than the fact that it was a strategy incorporated by species to deal with increased intraspecific competition.

Aggression, an emotion antithetical to compassion, actively governs violence. Like all means to an end, the efficacy of aggression depends significantly on its utilization. It continually contends with emotions that elicit other strategies such as cooperation, capitulation, or escape. It becomes optional and situationally dependent on the intuitive assessment of the reward gained to the risk incurred—the risk/reward ratio—along with the feasibility of other alternatives. Rodents, fish, or even humans do not consciously make well-calculated decisions; this is a cumulative effect of evolution over generations. Evolution has selected against maladaptive traits, allowing successful behavioural patterns to persist. If violence as a strategy works against the competition, it further propagates to the next generation, reinforcing the aggressive tendency of that gene-sharing group. This rationale is inherent to evolutionary theory, making aggression an innate trait strongly selected over millions of years.

SOMATIC NEEDS AND REPRODUCTIVE DESIRES

The somatic element, directly linked to the organism’s survivability, encompasses nourishment and shelter. This strong evolutionary selective force necessitated the monopolization of dense resource areas, resulting in established territories in some species. When resources were mobile, such as during herd migrations, hunting in others’ territories became necessary. Trespassing would often lead to violent conflict as it jeopardized the security of one’s somatic needs. Conversely, equally important in terms of evolutionary drive is the reproductive element, vital to the survivability of the species as a whole. It is not that species consciously desire more offspring, but the evolutionary mechanism in place causes individuals to desire sex. This fact is evident in the widespread practice of infanticide among many species to meet the growing population demand for environmental resources. If the societal demand for an offspring mediated libido, organisms would not engage in copulation under population abundance.

Additionally, there exists an asymmetry in nature between males and females, which forms the crux of male competition in most species. However, to understand sex differences, we must first examine their genesis — Why do two sexes exist?

ANISOGAMOUS SEXUAL REPRODUCTION: ASYMMETRICAL IN NATURE

Before a distinction between sex cells, all gametes were of the same size and shape in an isogamous state of affairs. Some cells on the larger side would have had an evolutionary advantage in terms of a greater initial nourishment supply to the embryo, leading to more developed offspring. This trend towards larger gametes would also propagate the evolution of exploiters, who could be of a smaller size and actively seeking out extra-large gametes, making them more numerous and mobile. The honest ones would not find the need to be mobile and would direct all their efforts to become as large as possible in order to produce a highly developed offspring. In turn, each group would push the other to the extreme, making one group extremely large, immobile, and scarce, while the other becomes smaller, faster, and more numerous. Two reproductive strategies took shape, the large-investment or ‘honest’ strategy and the small investment exploitative strategy. The strategies in the middle would fall short of the advantages the two extremes would reap. Anisogamous sexual reproduction is born, allowing genetic variation of unseen levels. The honest ones eventually formed the eggs, and the exploiters became the sperm. Conveniently, we use ‘female’ and ‘male’ to address these different reproductive strategies. My references to the terms have been and will be on this key anatomical difference, which forms the basis of the fundamental asymmetry discussed above. The numerous sperm cells compared to that of a few large eggs created a competition like no other. Causing a divergence in evolutionary adaptations that both groups would undertake throughout their course of life on Earth.

The large investment provided by females prior to the fertilization process became a significant commitment to the offspring. Nature does not permit such imbalances to exist. Therefore, females adopted various strategies in nature to ensure investment from males before copulation. A commonly known example is that of female praying mantises biting the head off of male mantises prior, during, or after the fertilization process. Interestingly, the male’s sexual performance does not decline even after losing its head. In fact, since the insect head has inhibitory nerve centres, she may even be improving his performance. In this manner, the female obtains an investment as it gets a nutritious meal used to nourish the offspring.

In the case of birds and mammals, let us look at two prominent strategies. One is the domestic-bliss strategy; females try to discern the male’s character by assessing his fidelity, more often adopted by species that gravitate towards pair-bonding. Female ‘coyness’ displayed in many species results from the domestic-bliss strategy. This entails long periods of courtship rituals, including considerable pre-copulation investment by the male. Some bird species do not copulate until the male has built the nest for the eggs.

Another is the he-man strategy, adopted in species where females raise the child by themselves to counter male abandonment. It entails obtaining strong genes through rigorous discrimination pre-copulation, ensuring a strong, healthy child who will not weigh the mother down when it comes to survival.

Additionally, as females carry a limited number of fertilized eggs and can be fertilized only once at a given time, they are logistically limited in the number of offspring they can have. The male, lacking this logistical burden, theoretically has no limit to the number of offspring he can have. With both sexes having the need to propagate their genes, two strategies took shape. Evolutionary, the reproductive capacity of a male is directly related to the ‘quantity’ of sex partners, while a female’s is dependent on the ‘quality’ of the partner. Therefore, the crucial limiting factor for a male’s reproductive success is competition from other males. One can imagine how that plays a role in inciting violent conflict.

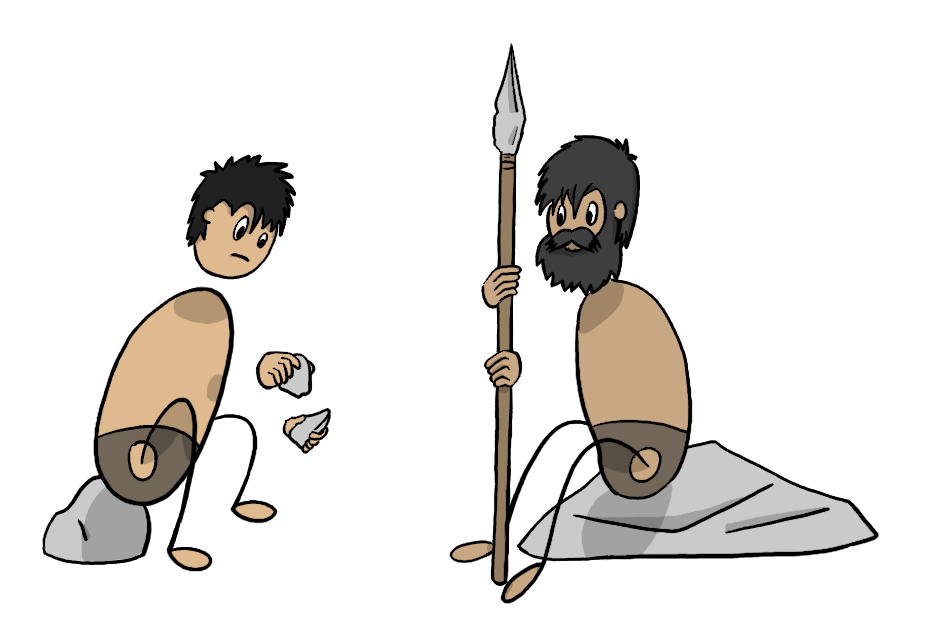

HUMANS: THE QUINTESSENTIAL FIRST STRIKE KILLERS

The risk-reward ratio dictates violent conflict in nature. Violent killing majorly occurs in asymmetrical fighting — conflict involving highly favourable odds. However, humans evolved to cheat the system itself. The enhanced tool-making ability of Homo sapiens made us extremely lethal creatures, with unprecedented first-strike capability, giving us the upper hand against creatures considerable times stronger than us. However, this came at a cost, a steady decrease in natural defences. While animals had sharp teeth, claws, and beaks as weapons, we had our tools, without which we were practically defenceless, but with which we could drive entire species out of existence. Add the unmatched lingual communication skills that enabled large group formation; we get a pack of highly proficient killers who never tire and always find a way.

This gives us a reasonable answer to the mysterious disappearance of every other human archaic species on Earth, most notably, the Homo neanderthalensis. The Homo sapiens’ enhanced in-group cooperation and superior first-strike capability made them the most dominant in terms of martial prowess of all the species under the genus Homo. Although a combination of reasons, like the spread of diseases from Africa, and climate change, can be associated with the demise of the archaic human species. Warfare must have played a crucial role, and the numerical superiority the Homo sapiens possessed must have been decisive in battle.

However, the massive first-strike capability completely changed the game of warfare between Homo sapiens. As humans were quite defenceless without their tools, the asymmetry in fighting regularly rotated. The victim today could be the raider tomorrow, shifting the risk/reward ratio back and forth. The fear of war breeds war, and we became insecure, fearful creatures.

CONCLUSION

In nature’s brutal competition for somatic needs and sexual desires, violence evolved as a strategy to mitigate the contest, while scarcity or abundance would further enhance it. Highly antithetical emotions evoke and suppress violence, making it both innate and optional, to be turned on and off in response to changes in the calculus of survival and reproduction.

The competition for resources gave rise to established territories protected by the pack against anyone thinking of threatening their resource security. On the other hand, the competition for females and the necessity to obtain strong survival genes by females made strength, size, and risk-taking behaviour recursive replicating forms within the male sex. How these factors affected warfare among humans will be discussed in the next article titled “Era of Hunter-gatherers”.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gat, Azar. War in human civilization. OUP Oxford, 2008.

Dawkins, Richard. The selfish gene. Oxford university press, 2016.